The Magic of Oneness

Dear Reader,

A short way down the trail from my cabin in rural Hawaii, there is a little old man who lives in a shack with a pig, three dogs, and four cats. Everyone worries that he is getting too frail to live in our remote off-grid community—carrying bags of dog food across the river in a faded green backpack, feeding his pig with overripe breadfruit he hauls down the trail in five-gallon buckets. Although we all lend a hand when we can, none of us are equipped to give him the kind of full-time care he’s getting closer and closer to needing.

A few weeks ago, he had a serious health crisis. My neighbor heard him shouting and called an ambulance, then lifted him into a wheelbarrow and rolled him all the way to the river, where the paramedics would be waiting to pick him up. That evening as we sat around under the monkeypod tree, my neighbors and I all wondered if he would come back. Perhaps he would go live in town, which was surely the right move for a person in his fragile state of health.

But just a few days later, I was on my way to check the water lines when I ran into him on the trail, a heavy bag of clothes and groceries in each hand. He was skinnier than ever, with pipe cleaners for legs and white hair sticking out from under his ballcap. He reminded me so much of the stray cat that had made its way back to my land even after I’d driven it three miles and several water crossings away. I stopped and offered to carry his bags, and he readily accepted. Even as I made this automatic offer, I felt a twinge of weariness—I was already so tired after a morning of working on my land in the hot sun, and still had much to do. After carrying the bags all the way to my neighbor’s place, I would have to return the way I had come and climb up the waterfall, which was my original errand. Although my body had extended itself reflexively to my neighbor’s aid, my mind began to protest at the cost.

Yet when I picked up my neighbor’s bags and felt the weight of them transfer from his body to my own, something miraculous happened: I had a sudden, visceral awareness that this transfer was taking place not between two distinct beings, but within a single organism. I wasn’t depleting “my” energy reserves—I was experiencing a kind of homeostasis, with energy flowing naturally to the place it was needed the most. Although my mind grumbled after the fact, my body had carried out the gesture automatically, the way certain trees will automatically send sugars to their less-healthy neighbors through roots and fungal networks underground.

Later, I wondered: did I stop and help my neighbor because I perceived the two of us to be a single organism, or did that brief and striking shift in perception arise from the physical act of making his burden my own?

Living off-grid, you can’t help but become aware of energy: where it comes from, where it goes, and the many ways it is used, recycled, and transformed. Light comes into the solar panels and the tool batteries greedily consume it, snug in their plastic chargers beside the power strip.

The energy stored in the tool batteries then goes into turning screws, cutting wood, and mowing grass. You spread the grass clippings in the garden to build the soil, and before you know it you have papayas, pumpkins, and sugar cane to feed your hungry body at the end of the day.

You scheme about ways to save energy—a more efficient light bulb, a lower-wattage computer monitor. Keeping your tools in a place that doesn’t require you to climb up and down a ladder fifteen times a day, which will cause you to burn fewer calories, which will make your stash of pumpkins last a couple of days longer, which means you won’t have to carry a pumpkin all the way home from your neighbor’s garden half a mile away, which means you will have more time and energy left over to finally fix your chainsaw, which means you can help your neighbor cut up the windfall bamboo, thus repaying the debt of energy left over from the time he helped you fix your solar system.

You notice the ways your neighbors are constantly transferring their energy to you—through their labor, their gifts of food and other resources, their encouragement on hard days. You transfer energy back in the form of your own gifts and words of encouragement, and the strength of your own body applied to a common task. The flow is organic, spontaneous, and unplanned. There is no ledger, yet all debts get paid; no accounting, and yet all that which is depleted gets restored.

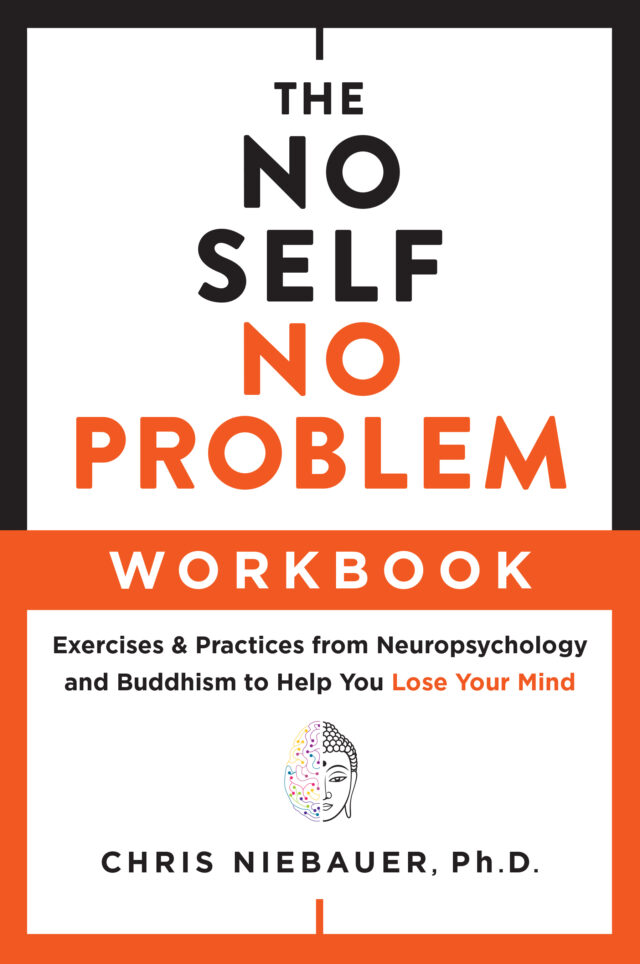

As an editor at Hierophant, I don’t frame roofs, cook meals, or harvest vegetables with the authors I work with, but there is nevertheless an aspect of shared labor, and therefore of community. When editing a manuscript, I receive the gift of the author’s wisdom; at the same time, I apply myself to the project of helping that author express their wisdom in the clearest possible way. Because many of the books I work with deal with spirituality, there is also a sense of chipping away at a shared mystery, and becoming part of one long chain of human endeavor to understand and celebrate the divine.

Recently, while editing a book chapter in which an author was describing a significant event in her life, I had an experience not terribly unlike the moment when I picked up my neighbor’s grocery bags. Gazing into space, as I do at regular intervals when I’m writing or editing, I tuned into the emotions the author was describing, allowing them to play out in my own body. As I pondered the idea she was trying to express and toyed with different ways of expressing it, I felt a sense of oneness with the work in which I forgot that an “author” and “editor” existed, and instead felt myself to be part of a unified field of humanity, all working on these deep problems of life, all shouldering the burden of being human together.

Although there are practical reasons for putting an author’s name on a book and giving that book its own title and cover art, this is really for the sake of convenience. As don Jose Ruiz likes to say, “We’re all working for the same boss.” Just as flowers come out of the earth, ideas come out of the great pool of human history. A flower couldn’t exist without the earth, and a book couldn’t exist without thousands of years of humans thinking, feeling, searching, and dreaming. Whether or not you ever have your name on a book, you’ve probably helped write one just by being alive. All labor is shared, whether we realize it or not—and realizing it can make us feel happier, more grateful, and more alive.

I’ll never forget the time I carpooled to a meeting in town with several of my neighbors. We were sitting in the bleachers of the high school gym, listening to some engineers give a presentation about plans for our road, when I happened to glance down. My feet and shins, I noticed, were caked with dried mud—the natural consequence of hiking through several streams on my way to the car. I rarely remember to rinse off my legs before going to town, and was feeling a little embarrassed at being seen this way by the town folks, when I saw that my neighbor’s feet were also brown with mud. Turning my head to look down the length of the bleacher, I saw that we all had the same dusty streaks on our calves and dried mud between our toes.

The sight of so many muddy legs nearly moved me to tears. I felt a sense of comfort, belonging, and something akin to pride. My neighbors knew the weight of a wheelbarrow, the value of a pig, a pumpkin, or a five-gallon bucket, the sound of rain on a metal roof. They knew what it was like to sit in your chair in a stupor at the end of a long day, too tired even to read; they knew the night-blooming flowers and the moon. When one of us was sick or weak, the rest of us didn’t carry that person’s burdens for them—we just carried them, period, because they were there to be carried, and we weren’t many beings, but one.

Readers, as we transition from spring to summer, may you all be supported by the energy of sun, earth, and community; and may your roots feed others, and be fed in return.

Sincerely,

Hilary Smith

Senior Editor, Hierophant Publishing

Click here to read Hilary's previous essay, "Hitchhiking to Freedom."