Acts of Love and Service

Dear readers,

Here in Hawaii, each island has a “wet” or windward side, and a “dry” or leeward side. The valley where I live is on the “wet” side. The forest here is graced with frequent rains and warm, damp winds. Mushrooms spring from rotting logs; ferns and flowers thrive; streams meander down the cliffside on their way to join the river that leads to the sea. I love the lush and misty mornings, and the rain that fills my catchment barrels and waters my garden. As for my possessions, and especially my books, they don’t fare as well in the relentless damp, which is forever making objects rust, mildew, or otherwise deteriorate in a variety of ways.

As an author and editor, I’ve spent most of my adult life lugging around a large collection of books: Chinese poetry, novels I keep meaning to reread, hefty tomes on technology, nature, and language. Since moving to the valley, however, I’ve realized that books aren’t meant to be collected—at least, not by me. They’re meant to be read before the warm, wet air speckles their pages with mildew or furs their jackets with a fine white coating of mold. My book collection, once substantial, now occupies one trim shelf—a strange state of affairs for a writer. The upside, however, is that when somebody gives me a book, I read it right away, before the local microorganisms have their way with it. A book feels like a flower, which will wilt, then rot—so I appreciate its fleeting presence all the more.

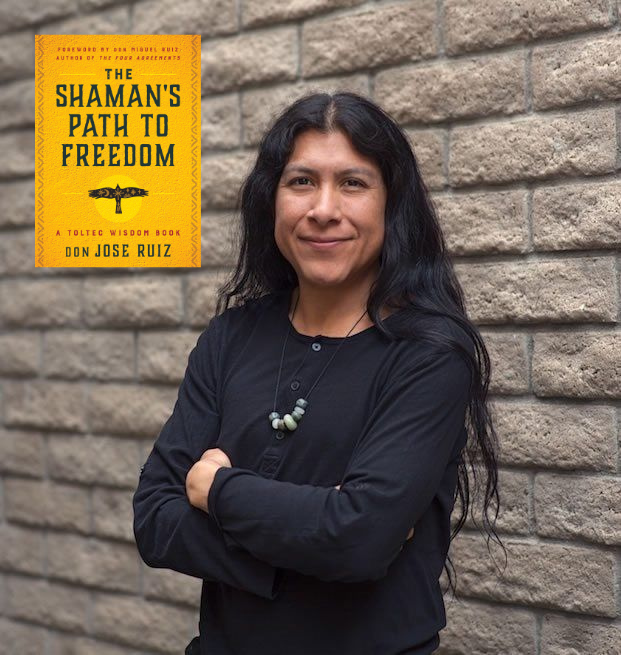

The last book I read was Loaves and Fishes: The Inspiring Story of the Catholic Worker Movement, by Dorothy Day—a gift from an acquaintance of mine. As the Senior Editor at Hierophant, I read a great variety of self-help and spirituality books, from a wide range of traditions. Although I could easily list all the Buddhist, shamanic, and New Age books I’ve read in the past year, I have to admit that was the first time in many years I’d read a Catholic one. In fact, the book had sat on my shelf for several months, in violation of my “read it right away” rule. I was afraid I wouldn’t like it, or that it would feel like church—a type of resistance I don’t usually bring to, say, the Zen books that come my way. But as Hierophant author and Toltec Shaman don Jose Ruiz would say, “We’re all working for the same boss.” Once I recognized my resistance, I took the book down and began to read.

Dorothy Day was a journalist who converted to Catholicism at the age of thirty, and co-founded a newspaper called The Catholic Worker, along with a social justice movement of the same name. With the help of a growing number of friends, she opened “houses of hospitality”—literal houses, apartments, and eventually, farms run by volunteers, where people impoverished by the Great Depression could get hot food, dry clothes, and a bed. In Loaves and Fishes, she talks in frank, no-nonsense language about the challenges of running these houses. She describes the difficult or unpleasant characters who moved in for months or years at a time—belligerent alcoholics, people suffering from severe mental illness, people who were selfish, grandiose, or downright mean.

It was against Day’s principles to turn anyone away, no matter how disruptive or destructive they were. She believed that humans were called to love one another, and she was determined to put this belief into practice, no matter how much it cost her at a personal level.

Far from making the path of radical love sound easy and attractive, she is unflinching in her account of how difficult it was. There were unpaid bills, evictions, theft and vandalism, and sleepless nights. Guests at the hospitality houses weren’t necessarily transformed by Day’s kindness; often, they wandered away just as cranky and irascible as they were when they showed up.

The path of love, in Day’s telling, isn’t only about working on oneself—it’s active service to the people who need our kindness and care the most, who often happen to be the people we find difficult or overwhelming. It’s doing things we don’t like to do, or which we even find unpleasant, giving up time, sleep, privacy, wealth, or comfort so that others may suffer less. Put another way, it’s a radical realization that there is no separation—that there is only one body of humanity which needs to be clothed, sheltered, and fed.

The day I finished reading Loaves and Fishes, I went to visit my neighbors, as I do several evenings a week. We sat around under the monkeypod trees, chatting about trucks and dogs and other features of rural life. Then one of my neighbors brought up the subject of the little old man who lives down the trail with a menagerie of dogs, cats, and pigs. As long as I’ve lived in the valley, he has been rickety, with a skinniness verging on the ethereal. We all have stories about finding him toppled over on the trail, pulled over by the weight of his enormous backpack, or sprawled in the river after his ankle turned on a rock. But in the past few months, he’s grown even more frail, and the question now arises of what to do about him. How can we help him? What do we owe him? Where do our responsibilities begin and end?

Six months ago, after he had a bad fall, a few neighbors found him housing closer to town, where he would no longer have to walk for miles to get basic supplies. But after just a few nights away, he made his way back to his hut in the forest, unwilling to leave the life and the home to which he was accustomed. We all confessed to leaving groceries at his gate; some neighbors brought him propane, and others cooked him hot meals. One neighbor raised the idea of repairing the old man’s hut, or moving him into an empty building where we could keep a closer eye on him—and wasn’t there an empty cabin on another neighbor’s land?

The neighbor in question protested. “You want him as your roommate, you take him!”

I couldn’t blame him. The truth is, we all had space to take in the old man, if we really wanted to. But the thought of having him there every day, with his dogs and pigs, his messiness and his needs, was daunting. Besides, the old man had already made it clear that he didn’t want to leave his hut, refusing the housing that had already been found for him.

“Do you guys even remember all the things he did?” my neighbor went on. “We’re not talking about some sweet old man, here.”

Indeed, the old man has caused a lot of harm over his lifetime. Although his age and frailty give him an aura of innocence, the truth is that he ruined many lives during his healthier years. How should that factor into how we treat him now? Should we bend over backwards to help him, or should we let him lie in the bed he’s made?

By the end of the evening, we hadn’t arrived at satisfying answers to these questions. But the next morning, and every morning after that, we all kept dropping groceries at his gate, just like before.

*

How can we practice love? Not just think about it, or write about it, but practice it in our everyday lives? How can we love others when it’s hard or inconvenient, or when they don’t deserve it as much as we think they should? How can we practice love when it’s unfair, outrageous, and uncomfortable?

I feel lucky to live in a community which challenges me to face these questions head-on, and to have a job which invites me to explore them in every book I read or edit. Whether you’re a shaman, a Buddhist, a Catholic like Dorothy Day, or something entirely different, the work of love is never-ending. Like a beautiful mountain we set out to climb, it has difficult terrain we couldn’t anticipate when we were only gazing at it from a distance: rocky slopes and perilous crossings that put our hearts and bodies to the test. We do the best we can with the knowledge and resources at our disposal, and seek support and inspiration from the fellow climbers we encounter along the way. Most of the time, the answers are simpler than we make them out to be. Put one foot in front of the other. Bring the groceries. Feed the dogs. The outcomes of these actions aren’t ours to decide.

This spring, I hope you all find wildflowers on your mountain of love, even as you make your way through the tricky parts—and that the love you share comes back to you many times over, whenever you need it the most.

Sincerely,

Hilary T. Smith

Senior Editor, Hierophant Publishing